Repatriating “Muddy Ridge” on the Wind River Indian Reservation

Greater Yellowstone’s remarkable lands—whether public, private, or on reservations—provide spiritual and cultural connections paramount to mental health and livelihoods. For Tribal Nations, lands and related land deals are reminders of the federal government’s continued deceitful actions and attempted assimilations of Indigenous People.

For the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes of the Wind River Indian Reservation (WRIR)—a key landscape in Greater Yellowstone—there is opportunity to right one wrong of the past. GYC is supporting the Tribes in their quest to reclaim 111,000 acres of homesteaded land under the Excess Property Act.

To understand the totality of this request means we need to go back to the 19th and early 20th century, when the Wind River Indian Reservation still embraced over 3,000 square miles and hosted a diverse array of resources, from high mountains to rangeland to irrigable soils, with abundant wildlife, oil and gas, and water, enough to sustain a way of life that was rich in culture, tradition, food, and more.

In 1863, the Eastern Shoshone Tribe initially signed a Treaty with the U.S. government for approximately 44 million acres. Despite promises from the U.S. government, the Shoshone Tribe was forced to enter another Treaty just five years later, for the current location of the Wind River Indian Reservation and a reduction of 1/20th the size of its original boundary. (Read additional details about these two Treaties here.) In 1878, due to more broken promises by the U.S. government at the time, the Northern Arapaho, once enemies of the Eastern Shoshone and with different histories and traditions, were permanently settled on the Wind River Indian Reservation

Just a few years later, on March 3, 1905, Congress opened the lands of the Wind River Indian Reservation to settlement by non-Indians. This settlement was primarily for the purposes of agriculture, and in the arid Wind River Basin of Wyoming, successful agriculture required irrigation.

In 1918, the U.S. government withdrew lands for the purposes of what would become the Riverton Reclamation Project (Riverton Project), which developed irrigation infrastructure and water storage facilities. Further withdrawals by Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) occurred in 1940 around Bull Lake for Bull Lake Reservoir, which is an important fishery to the Tribes, and in 1952 around Boysen Reservoir. These withdrawals, and the unused lands still in U.S. control, form the basis of the Tribes’ request.

Since 1939, the Tribes have been interested in, and pursued, the return of lands withdrawn for a variety of reasons. In 1939, an Act of Congress provided for the restoration of all undisposed lands within the reservation that were opened for settlement, but all lands within the reclamation project were excluded from restoration at the time. The restorations as a result of the 1939 act were significant, but left the U.S. government in control of the unused lands in the reclamation project.

Successful restorations of 70,000 acres in 1953 around Boysen Reservoir and more recently 120 acres west of Thermopolis in 1988 were returned to the Tribes through the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act (also known as the Excess Property Act), however, the lands at Muddy Ridge near the Riverton Reclamation Project have remained elusive.

In 1970, the reauthorization act of the Riverton Project recognized fish and wildlife conservation as an authorized purpose of the project. Despite this authorized purpose, it does not preclude the return of the lands to the Tribes. Department of Interior policy summarizes that if another agency is willing to fulfill the agreement, then the agreement is not a basis for continuing withdrawal.

Today, the Tribes partner with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to manage wildlife on the reservation and have worked closely with Wyoming Game and Fish. Such arrangements, in combination with the Department of Interior policy that an authorized purpose is not enough to form basis for retention, shows the lands should be returned to the Tribes.

There are three parcels that make up the 111,000-acre “Muddy Ridge” request. Two of the parcels are relatively remote with access controlled or de facto controlled by the Tribes. The third is north of the current dam site, where the State has recreational facilities through a lease with the federal government.

GYC is supporting the two Tribes with this request. We are working alongside both Tribes to ask the Department of Interior to bring resolution to this decades-old matter by repatriating these lands in support of Treaty Rights and Tribal Sovereignty.

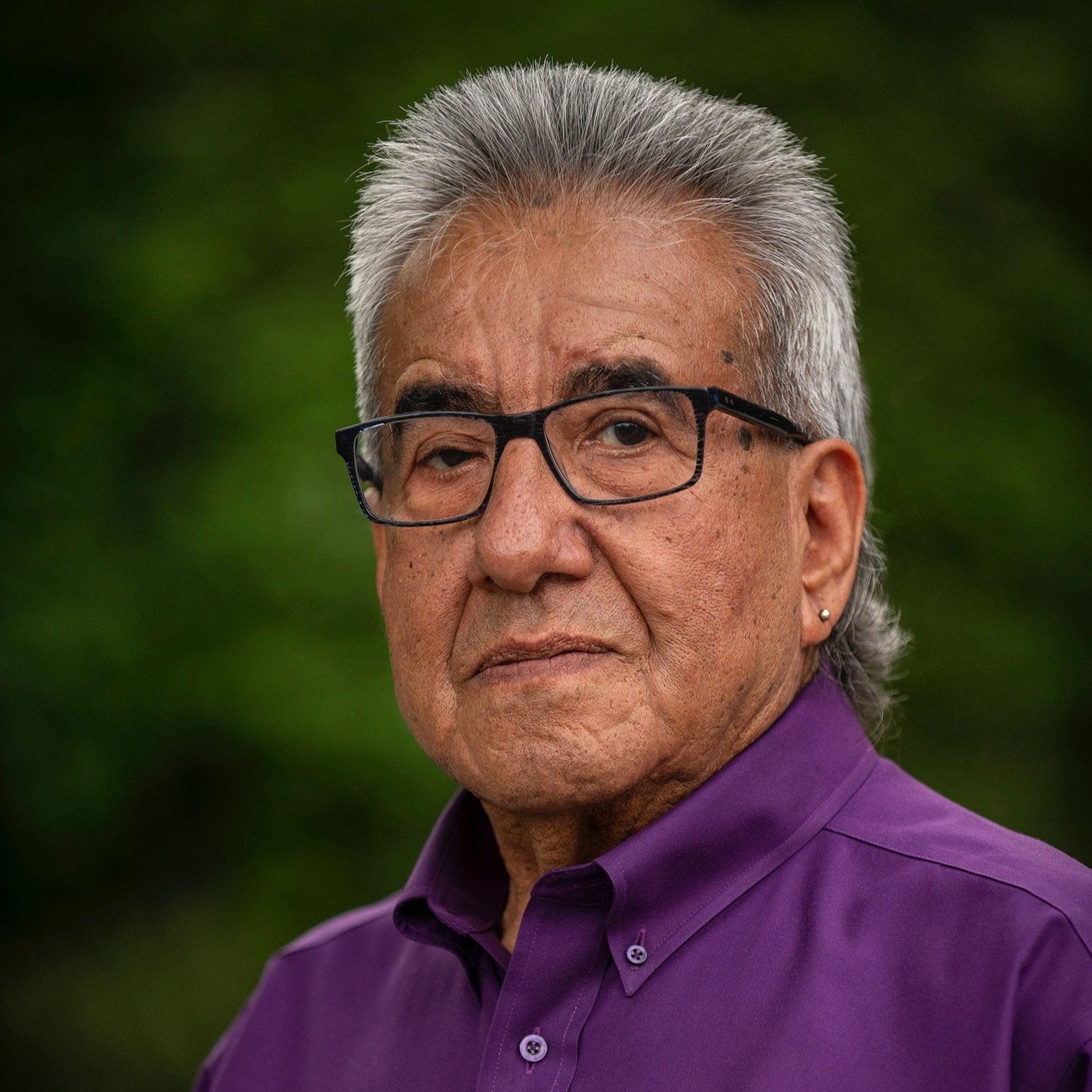

—Wes Martel, senior Wind River conservation associate (Eastern Shoshone)

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is the land of 49+ Indigenous Tribes who maintain current and ancestral connections to the lands, waters, wildlife, plants, and more.

Banner photo: Angela Burgess, USFWS