Treaty Rights, Winters Doctrine, and Federal Reserved Indian Water Rights

Water is the gift of life. It is my relative. It gives me energy and healing. It provides me cultural and spiritual connections to my ancestors. It is my ancestor. It is a part of my being and soul. We were all born in water. It is the most valuable and precious resource for everyone and everything on the planet.

As an Eastern Shoshone Tribal Member and Elder on the Wind River Reservation, it has been my life’s work to ensure water remains a Treaty right and a human right for my people. On August 23, 2022, I spoke about these efforts and the history of water on the Wind River Reservation as part of the Office of Community Service’s World Water Week.

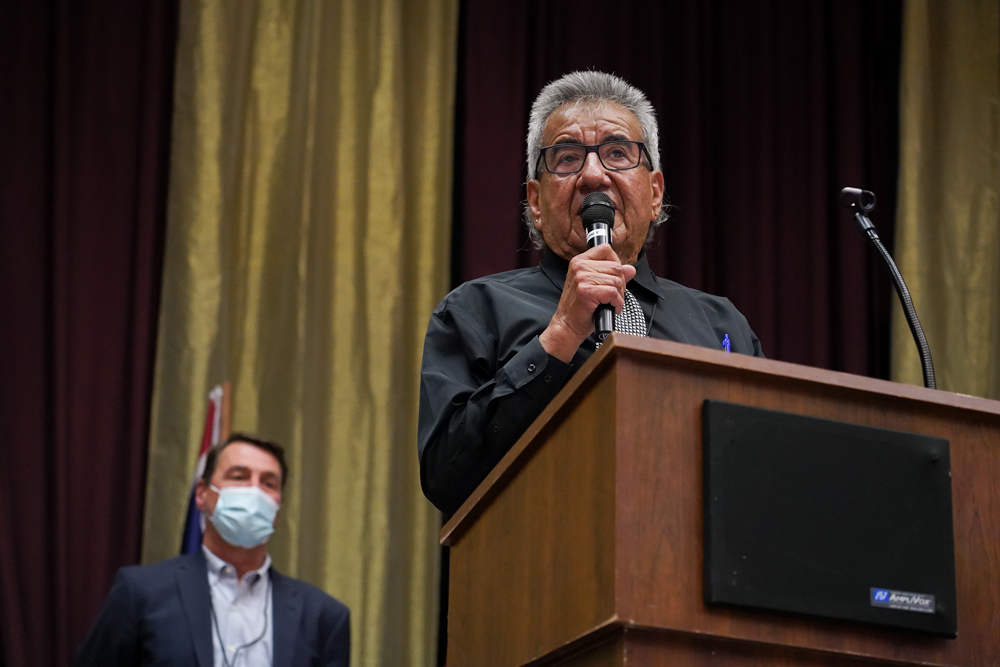

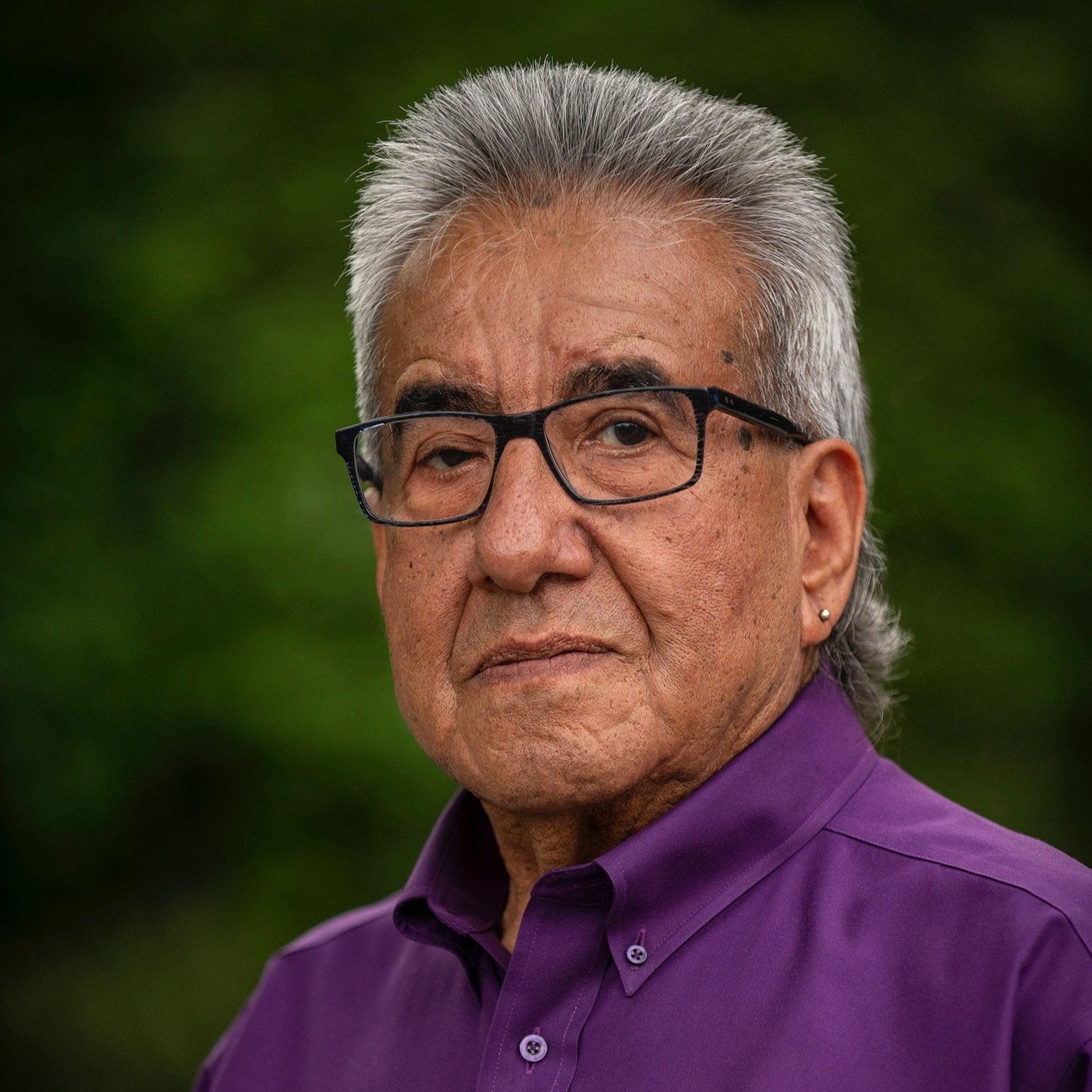

GYC’s senior Wind River Conservation associate Wes Martel speaks at the Wind River Inter-Tribal Gathering from June 2022. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

To summarize my presentation, I focused on the history of the Wind River Reservation as an example of what colonization and failure to honor Treaties has done to Indigenous People, especially the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho. As you read on, I hope you will learn about the history of water in the United States and on reservations, as well as what we're doing now to make positive changes for the future of Indigenous People.

When our ancestors signed Treaties, they were trying to protect our way of life. The Eastern Shoshone Treaty of 1863 established the Wind River Reservation of 44,000,000 acres that took up parts of Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, and Colorado.

Five years later, the Treaty of 1868 reduced the size to just 2,500,000 acres. The reasoning by the United States at the time for reducing the size of the Wind River Reservation was to protect the Shoshone people from lawbreakers. Penalize the rightful landowners, reward the violators of the Treaty and the law! This is backward colonizer/Christian thinking that has been a curse on Indigenous People since 1492.

Over the past 100 years, many U.S. federal acts, policies, and projects—stemmed in racism—have attempted to oppress our people and limit access to land and water. These include:

The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887

The Reclamation Act of 1902

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934

The Rogers C. B. Morton Moratorium of 1973

On the Wind River Reservation, we have experienced additional difficulties, including:

The Construction of Diversion Dam in 1919

The Big-Horn Adjudication Case of 1977 (ruling in favor of the State of Wyoming over the Wind River Reservation and Winters Doctrine)

That said, we want to celebrate the positives of some efforts, including:

Lifting of the Morton Moratorium (2022)

The United States vs. Winters was a win for Tribal Nations. Under western water law and west of the Mississippi, this court case established the Winters Doctrine, which recognizes and enforces prior appropriation; Tribes have senior Treaty rights to water. First in time, first in right. These aren’t just any old state water rights, these are Treaty rights, Federal Reserved Indian Water Rights, with the Winters Doctrine, is paramount for the protection of an extremely valuable trust resource, Indian water.

We can also be grateful to Interior Secretary Deb Halaand for lifting the Morton Moratorium on April 6, 2022, which previously prohibited Tribes from adopting Water Codes. Finally, it took an Indian woman to recognize the importance of the federal government’s role in protecting Federal Reserved Indian Water Rights.

Crowheart Butte on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. (Photo Julie Falk/Flickr Creative Commons)

More recently, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition has been supporting the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho in their quest to reclaim 111,000 acres of homesteaded land on the Wind River Reservation that the Bureau of Reclamation declared was in “excess” in 1994. According to the Bureau, this land is no longer needed to fulfill the purpose of the Reclamation Act of 1902. And, according to the Act, land is supposed to revert back to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in trust for the Tribes. Luckily, we have been in recent discussions with the Department of Interior to bring resolution to this decades-old matter.

The Greater Yellowstone Coalition is also asking the federal government to review the social, economic, and cultural injustice of Wyoming’s Diversion Dam on the main stem of the Big Wind River and its related Wyoming Canal project. These irrigation systems have diverted water—life’s most important natural resource—away from the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho people on the Wind River Reservation. It has been re-routing water to non-Indian people downstream for more than 100 years. We all deserve water. Water is a human right, and it is a Treaty right. Without access to water, the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes have suffered immeasurably as a result. We want to help restore the Big Wind River and all of its cultural, spiritual, and economic attributes to the Tribes of the Wind River Reservation and its surrounding neighbors.

The Big Wind River on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

Overall, it is my belief that the United States must understand its role in honoring and recognizing Treaties. We are hopeful we will finally see welcome changes to support Indigenous Peoples’ way of life. Improved access and use to Wind River’s water is just one of the ways we can begin to do better for Indigenous People.

Hahou (thank you).

—Wes Martel, Senior Wind River Conservation Associate (Eastern Shoshone)

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is the land of 49+ Indigenous Tribes who maintain current and ancestral connections to the lands, waters, wildlife, plants, and more.