Collaboration is key in grizzly country

On a clear morning in late May my coworker Emmy and I pull into the gravel parking lot in front of the Alder fire hall in Montana’s Ruby Valley. The lot is already lined with pickup trucks, backed-in and spackled with the mud of recent rains. Inside the building, small groups of ranchers and researchers stand in the low hum of congenial conversation. A cistern of thick black coffee perches on the countertop window leading to a spare, no-nonsense fire hall kitchen. A flyer posted on the wall states masks are now optional for the vaccinated.

Emmy and I are met by three of our coworkers who have helped facilitate this gathering – Montana Conservation Coordinator Darcie Warden, Senior Wildlife Program Associate Brooke Shifrin, and Wildlife Program Associate Blakeley Adkins. It’s good – and frankly novel – to see them in person, barefaced and smiling.

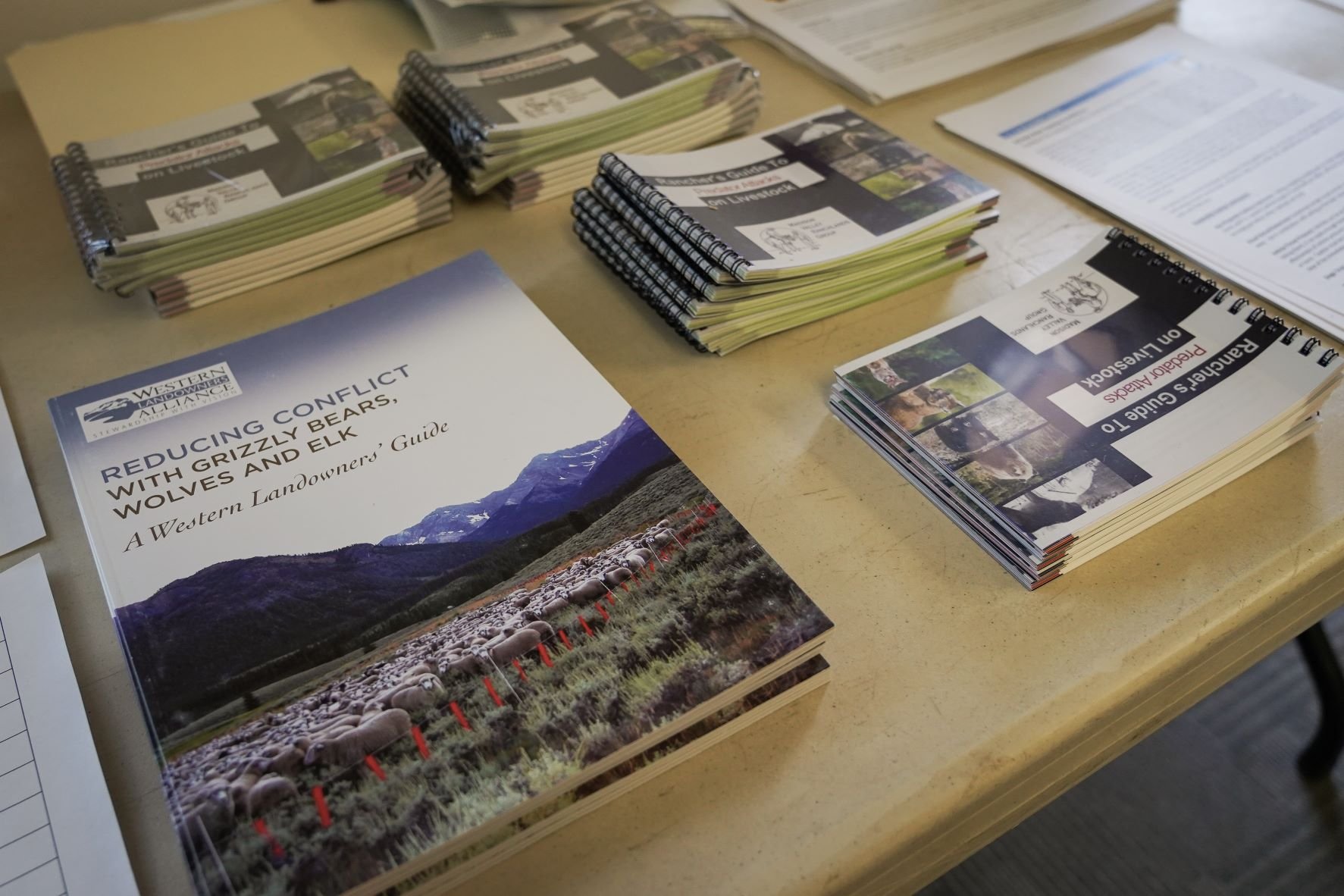

Educational materials for workshop attendees on safely managing livestock in Greater Yellowstone. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

Everyone is here for the same reason – to talk about how to more safely and effectively manage livestock in grizzly country. The gathering was first conceived of by cowhands Amber Mason and Andy Peterson of Ruby Dell Ranch. Each summer Amber and Andy drive Ruby Dell’s cattle to the ranch’s grazing allotment in the rugged Gravelly Mountains. As Yellowstone grizzly populations have started to recover and expand back into their historic habitat, encounters are on the rise in the area. Amber and Andy saw an opportunity there for shared learning centered on how to protect livestock – and thus the livelihoods of ranchers – from increasing numbers of wild predators. Erica Nunlist with the Centennial Valley Association helped develop the idea further, and GYC provided resources and worked out a place to convene.

The question we’re all here to work through is, how do we ensure that ranchers and bears are both able to stay safe and make their livings on this wild landscape? How do we, in short, learn to coexist?

A snapshot of the participants at the workshop. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

Once the last few participants have come through the front door, scraping dried mud off their boots on the concrete slab just outside, we get started.

Steve Primm kicks off the workshop. Steve, who has wildlife management and conflict mitigation credentials a mile long, lends his expertise to several of GYC’s on-the-ground conflict prevention projects, from bear-proofing campgrounds to building wildlife-friendly fences. He is that rare combination of big picture thinker and skilled hands-on implementor.

Steve reiterates that we are here to talk about “how to have grizzlies and wolves on the landscape while ensuring ranching is still a viable livelihood.” He introduces our main speaker, Whit Hibbard, a fourth generation Montana cattle and sheep rancher and expert in low-stress livestock handling. A lean man with angular features and a tidy mustache, Whit wouldn’t look out of place onscreen in a classic Western. On the projector screen at the front of the room, the title of his presentation appears: “Stockmanship in Grizzly Country.”

Rancher and low-stress livestock handling expert Whit Hibbard presents to the crowd of ranchers and cowhands. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

The thrust of Whit’s philosophy as it relates to our topic for today is this: A herd of cattle that has been managed in such a way as to encourage and preserve their natural herding instincts is its own best defense against predation. Bunched together on the landscape, they are less likely to run into predators than a dispersed herd, and more likely to mount a defense if they do. Cows managed using low-stress techniques are also easier to handle, gain and maintain weight more readily, and provide a better return for the rancher.

GYC’s Communications Coordinator Kristin Kuhn and Montana Conservation Coordinator Darcie Warden listen in on Whit’s presentation. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

Whit shares a comprehensive list of the principles behind low-stress handling practices and illustrates their outcomes with a series of videos. The first shows the scene of a more conventional approach to handling stock – plumes of dust rising as animals surge through fenced enclosures, bellowing. Gates clang, voices holler, and crops slap against flanks. The next video shows the same event – bringing cattle in for shipping - utilizing low-stress handling techniques. It makes for decidedly less exciting television. Cows move fluidly from pasture to pen. The camera picks up the sound of the wind, an occasional moo, a chirping bird. These animals don’t build the same stress associations with being in close proximity to one another, and are more likely to keep each other close while at pasture.

We break for lunch. Beloved local café Shovel & Spoon has catered, and dishes out generous portions of coleslaw and macaroni salad on the side of pulled pork sandwiches. Plates in hand, everyone starts moving toward to front door, drawn outside by the cool breeze and spring sunshine. I overhear more than one good-natured joke about low-stress herding of the lunch line.

(L-R) GYC’s Kristin Kuhn, Darcie Warden, and wildlife management contractor Steve Primm wait for an opportunity to grab some lunch. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

After lunch, Whit takes the tools and techniques we’ve been discussing and puts them together into real world scenarios a cowhand might encounter on the range. After he wraps up, a representative from Wildlife Services stands up to go through the protocol for what to document and who to call should a rider find dead livestock. It’s an encouraging instance of an agency representative and the constituents they serve communicating face-to-face. This kind of proactive approach to shared learning and expectation-setting helps both agency personnel and ranchers prepare to deal with livestock issues before they happen. After all, communication is a big challenge when it comes to livestock predation.

Once there’s a suspected kill, the clock starts ticking on a rancher’s ability to collect the evidence it takes to have the kill confirmed (and thus, be compensated for the loss) because carcasses don’t last long in a landscape full of scavenging wildlife. Out here in the remote ranges that surround the Ruby Valley, reliable cell service isn’t exactly ubiquitous. The more human-to-human connections made and real-world discussions had in workshops like this one, the better. It’s heartening to see hands shaken and numbers exchanged. Real people engaged in real conversation, discussing how to best tackle complex and often emotional situations together.

Topics at the workshop included how to move livestock in a low-stress manner, how to report and document a depredation in the field, and how to stay alert and safe in bear country. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

Naturally, the conversation turns to human safety. Sticking around a bear kill to document evidence of predation is dangerous so there’s tension that needs to be resolved there. It’s easier to do that face-to-face as well.

As Emmy and I make our way back to Bozeman that afternoon – driving through all the late May splendor of southwest Montana along the Madison River - we discuss how the workshop went. As we talk, Brooke’s assessment of the importance of gatherings like this comes to mind:

“The only way bears will stay safe on connected landscapes is if they can coexist with people. That only happens when folks commit to being creative and navigating these challenges together. That happens in these workshops. This workshop was asked for by the people working in grizzly country every day. We just provide the resources and convening capacity.”

So here we are. Holding space for each other and we talk about holding space for bears. Acknowledging that we all have a place on this landscape as long as we support one another and learn to live together.

“When we get together and have dialogue, we get to think critically about risk, share stories, and share ideas. Every time we have a dialogue, we get closer to real solutions. This is forever work. And we are committed to keeping after it.”

A joyous GYC post-vaccination photo op! (L-R) GYC staff Darcie Warden, Brooke Shifrin, and Blakeley Adkins pose outside the Alder fire hall. (Photo GYC/Emmy Reed)

GYC is committed to keeping people safe, wildlife alive, and livelihoods intact in Greater Yellowstone through our human-wildlife conflict reduction work.

—Kristin Kuhn, Communications Coordinator