How Roadkill Helps Build Wildlife Crossings in Montana

Decked out in an orange, high-viz vest with neon pink spray paint in hand, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition’s Blakeley Adkins steps out of the car and onto the highway that takes you to the north entrance of Yellowstone National Park. She ventures down the roadside ravine, aiming for a crumpled deer carcass.

Over the roar of cars flying by at 70 miles per hour and the echo of the rumble strip, she tells me the spray paint is used to mark the foot or head of the animal to make sure it’s not counted twice.

Today, we are surveying roadkill – and live animals. Shaking the can of spray paint, she marks what remains of the deer.

Blakeley Adkins, GYC’s The Volgenau Foundation Wildlife Conservation Associate, walks to mark a deer carcass with spray paint during a weekly wildlife survey. (Photo GYC/London Bernier)

For more than four years, Yellowstone Safe Passages (YSP) has been surveying roadkill and live animals once a week. Blakeley represents the Greater Yellowstone Coalition in YSP, a community-led initiative working to enhance the safety of people and wildlife traveling along Highway 89.

For the last two years, Casey Rifkin has led these surveys, only missing one when she’s out of town. That’s where Blakeley and I enter the scene. Surveyors travel the stretch of U.S. Highway 89 between Livingston and Gardiner, Montana, eyes peeled for creatures alive and dead. They have recorded an incredible diversity of wildlife – raptors, skunks, fox, coyote, bears, cougar, beaver, bison, turtles, and most commonly, deer and elk.

On Casey’s first day of survey training, the first animal they came across was a black bear that had been struck by a car.

With the spray paint applied, we pull out Blakeley’s phone to enter data about the deer into the group’s ArcGIS data collection app. Species? Deer. Unclear if it’s a muley or white tail. Carcass, wildlife crossing the road, or wildlife within 100 meters of the roadway? Carcass. How many animals were observed? One. Her phone autofills the date, time, and location. Signaling back onto the highway, we continue our drive.

While collecting carcass data can be gruesome and disheartening, every data point is helping inform Yellowstone Safe Passages about the areas that see the most accidents – and the areas where wildlife crossings structures will be most effective along Highway 89. This deer will be added to a suite of more than 7,000 wildlife observations collected since the spring of 2020 to help YSP keep wildlife alive and families safe on the road.

Blakeley began conducting these surveys before joining GYC as The Volgenau Foundation Wildlife Conservation Associate and has a keen eye for pointing out camouflaged creatures on the farm fields and sagebrush hillsides that flank the highway.

How many mule deer can you spot in this photo? (Hint: They sure can look like rocks.) (Photo GYC/London Bernier)

For those who call Montana – and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem – home, this skill is born out of necessity. Keeping an eye out for wildlife can be the difference between making it home safe and being on the phone with the insurance company at best. But no matter how careful and vigilant you are, accidents with wildlife are the unfortunate norm for Paradise Valley residents. As Casey tells me, it’s a game of statistics – if you drive here long enough, you will hit something.

Blakeley herself is part of the vast majority of folks living in the valley who have been in an accident involving wildlife on Highway 89. Driving through the dark and a Montana blizzard a few years before making Paradise Valley home, Blakeley’s Jeep Cherokee and a bison collided on this road. Blakeley fortunately walked away, but her car and the bison weren’t so lucky. Along the highway between Livingston and Gardiner, 50 percent of accidents involve wildlife, which is five times the state average and 10 times the national average. YSP estimates this has cost community members and visitors $32 million in vehicle damage over the past 10 years.

As we travel south on the highway toward Gardiner, we pass a digital sign that reads “Wildlife on Roadway” welcoming us to Yankee Jim Canyon. We make it through a couple of tight, blind bends before two bighorn sheep appear on the hillside next to the road. Stopping at one of the turns-offs overlooking the Yellowstone River, we enter another data point into Blakeley’s phone and document the pair.

A pair of bighorn sheep graze next to Highway 89 as a truck passes by. (Photo GYC/London Bernier)

Between Yankee Jim Canyon and Gardiner, we see hundreds of elk varying distances from the road. At one point, we hit the flashers and wait as a group of elk amble across the roadway. Members of the herd congregate on both sides of the highway, grazing, absorbing sun, and getting a little too close to pavement for everyone’s comfort. More alive data points for us.

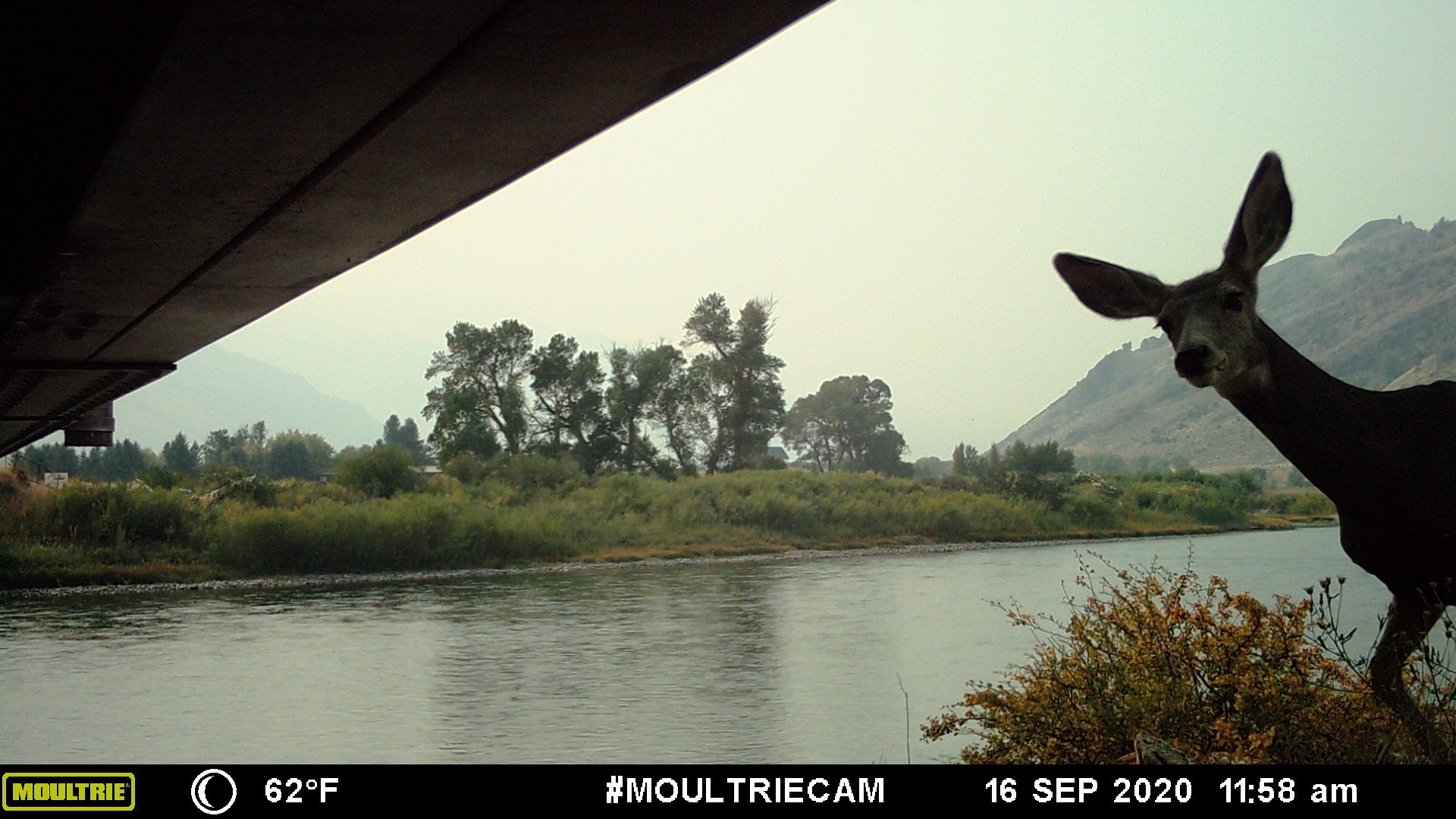

These surveys are not the only data being collected along this stretch of highway. YSP has two game cameras set up under highway bridges that wildlife already use as safe ways to cross. YSP has also recruited community members who travel Highway 89 as citizen scientists to be their everyday eyes on the ground. (If you want to be a citizen scientist, join us!) In addition to YSP, the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) records and picks up carcasses twice a week.

Having a diversity of data sets is key. In the four years YSP has been collecting data, their surveys have resulted in almost eight times more elk and deer roadkill surveyed compared to the MDT carcass data.

Wildlife use a Highway 89 bridge to safely traverse the busy road. (Photos Yellowstone Safe Passages)

The YSP and MDT data, and more, was put to use last year in a milestone step toward making the highway safer for people and wildlife. In early 2024, YSP released an assessment of Highway 89 between Livingston and Gardiner that identified seven priority sites for addressing wildlife accidents and a suite of potential solutions for each one ranging from new overpasses and underpasses, to retrofits to existing structures, animal detection systems, and fencing.

With a top priority site – called Dome Mountain – in their sights, YSP is making strides toward building two wildlife overpasses. In the fall of 2024, the group received state funding to conduct what’s called an engineering feasibility study. An engineering feasibility study is needed to break ground on a wildlife crossing project. This step determines if a project can move forward to design and construction.

On our return to Livingston, we stop at the Dome Mountain site, and Blakeley points out where one overpass would be built. As we step out of the car, a group of mule deer pick their heads up from grazing. Most winter days, you’ll see a mass of elk here too.

Looking down, the side of the highway is littered with bones. From the car, it’s nearly impossible to see the evidence left behind from wildlife-vehicle collisions – or so it seems to my untrained eyes. Talking to Casey, there’s plenty of evidence left behind when someone hits an animal, if you know what to look for. Casey tells me nature always provides, and that birds often help her to find roadkill that may be otherwise undetectable while driving down the highway. Skid marks and blood splatter are also indicators.

As we stand on the side of the highway, Blakeley tells me that when she stops to record and mark a carcass, more often than not, she sees evidence of other roadkill or wildlife movement like bones, old pelts, or game trails.

If the wildlife crossing structures are built at Dome Mountain and fencing is installed on either side to funnel wildlife, wildlife-vehicle collisions will decrease by up to 97 percent.

This roadkill data is helping inform Yellowstone Safe Passages about the areas that see the most accidents – and the areas where wildlife crossings structures will be most effective along Highway 89. (Photos GYC/London Bernier and GYC/Blakeley Adkins)

While we wait to hear whether Dome Mountain will continue clearing hurdles on the path to becoming reality, the wildlife surveys will continue. With more than 100 surveys under her belt, Casey sees this work as a rare opportunity to have such an effective impact in one lifetime. A wildlife crossing in Paradise Valley would save hundreds of animals every year and keep people safe.

Your support makes work like this possible. Thank you for being an advocate for Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife and communities!

—London Bernier, Communications Associate (Bozeman, Montana)